Two weeks ago, 50,000 runners took to the streets of London to run the TCS London Marathon. Both of the Elite race winners, Alexander Munyao and Peres Jepchirchir (who set a new world record), were wearing the newest Adidas racing shoes – the ‘Adizero Adios Pro Evo 1’.

In fact, almost all of the top ten finishers in both the men’s and women’s races were wearing Adidas shoes. But it wasn’t that long ago that Nike had a stranglehold on the racing shoe market. In this article, we will briefly examine the effect of Nike’s and Adidas’ patents on the emerging ‘super shoe’ market. We will consider how Nike was able to capitalise on taking the first move and how other brands were able to respond.

In 2016, a paradigm shift occurred in the running world when Nike unveiled the Vaporfly 4% prototype. Traditional racing shoes favoured a lightweight and minimalist design. In stark contrast, the Vaporfly featured a comparatively massive 39 mm stack height and a carbon plate that spanned the length of the shoe. This was the first ‘super shoe’.

The combination of the shoe’s lightweight polymer (Pebax®) foam and a carbon plate was said to improve a runner’s efficiency by 4% on average – hence the shoe’s name, ‘Vaporfly 4%’. It was also suggested that the shape and angle of the carbon plate contributed significantly to the efficiency gain because, amongst other reasons, it orientates the wearer’s foot, promoting efficient landing and pressing off with each step.

The shoe was immediately successful competitively and later commercially once it was publicly released. This left Nike’s competitors scrambling to provide competitive alternatives.

The sole issue

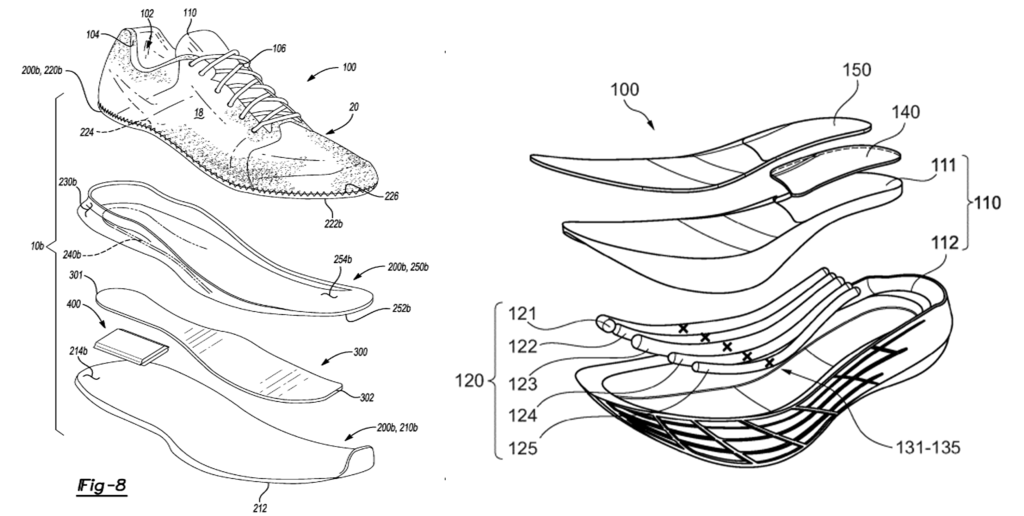

In addition to the polymer foam and material of the shoe’s upper, the shape of the Vaporfly’s plate is claimed to have a big influence on its performance. This aspect of the shoe was protected by multiple patents filed in numerous jurisdictions. One such patent is US10,448,704B2, which describes a sole structure comprising a plate disposed between the outsole and the upper, with a concave portion including a constant radius of curvature, a convex portion, a substantially flat portion and a first cushioning layer disposed between the concave portion and the upper.

Clearly, the patent covers a lot of ground. However, in 2024, there are over ten different brands of super shoe on the market. Each of these brands will have needed to consider Nike’s multiple patents that covered the Vaporfly’s technology or run the risk of potentially costly legal battles. This is in addition to navigating the restrictions on stack height and the number of plates more recently introduced by World Athletics in 2020.[1]

Consider, for example, Adidas’ contribution to the super shoe community. The Adizero Adios has become a serious competitor to the Nike super shoes since its first release in 2020. Rather than a single plate, the shoes feature a number of carbon-based rods that Adidas has titled ‘ENERGYRODS’.

The rods are said to mirror the metatarsal bones of an athlete’s foot, offering potentially more flexibility than a single, coherent plate. Adidas has protected this technology through multiple patents, including EP3868243B1, claim 1 of which specifies, amongst other features, at least two reinforcing members extending in the front half of the sole, wherein the reinforcing members are adapted to be independently deflected.

Contrasting approaches to shoe sole technology: on the left, Figure 8 of Nike’s US10,448,704B2 patent featuring a rigid plate. On the right, Figure 1a of Adidas’ EP3868243B1 patent featuring multiple rods.

Regardless of whether the rods were designed specifically in view of Nike’s IP position or from first principles, they are clearly effective from a commercial and competitive perspective. They seemingly use a different concept from Nike’s plate and comply with the restrictions brought in by World Athletics. To top it off, Adidas has made the rods a major part of the marketing for their racing shoes.

Other players in the market have now similarly found their own niche. Saucony, for example, has developed a fork-shaped plate, which they argue allows for a more aggressive ‘toe off’. Even this seemingly small modification could potentially be considered novel and inventive over the existing technology, particularly if a surprising benefit is achieved (such as improved running efficiency).

Patenting perspective

The fact that other companies have been able to bring super shoe technology to the market doesn’t mean Nike’s early patent protection was unsuccessful – far from it. A key purpose of a patent is to prevent competitors from gaining an unfair advantage from the patentee’s hard work. By patenting its technology, Nike forced its competitors to innovate further, potentially delaying their entry into the super shoe market and providing Nike with an extended period of time to benefit from being first to market. As outlined above, the Vaporfly 4% was first introduced in 2016, but it wasn’t until 2020 that Adidas unveiled their ENERGYROD concept.

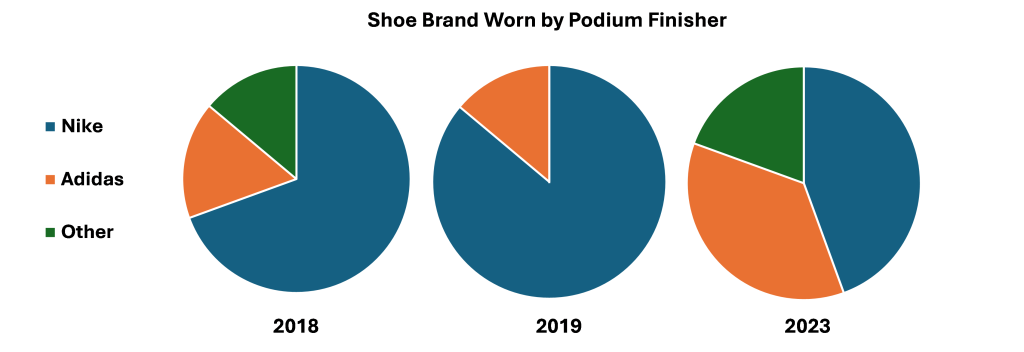

During that time, Nike dominated the racing shoe market. This was reflected by the proportion of athletes wearing Nike shoes that featured on the podiums (top-three finishers) of the World Marathon Majors (Tokyo, Boston, London, Berlin, Chicago and New York) in that time period.

Competitive dominance: distribution of shoe brands worn by podium finishers of World Marathon Majors in 2018, 2019 and 2023.[2]

Of course, Nike shoes were already a popular choice before the super shoe technology was unveiled, but alternative brands, including Adidas, remained competitive. From 2018 to 2020, Nike’s first-to-market benefit to the new super shoe sector resulted in almost all of the top-finishing athletes wearing a version of its shoes. Some competing brands even allowed their athletes to wear Nike shoes with the logo covered, acknowledging the significant advantage the shoes brought.

Since 2020 and the emergence of competing super shoes, Nike’s dominance has faded somewhat. In particular, Adidas has become a much more viable alternative for top competitors, as highlighted by last weekend’s results in the London Marathon. Adidas appears to have successfully navigated the more restricted patent landscape to produce a successful competing product.

In summary, Nike clearly saw a benefit from being the first to market with the Vaporfly 4%, and their IP rights will have undoubtedly helped them to capitalise on their advantage. Their IP may also put them in a continuing position to license their technology to other brands in return for royalties. For example, even if competitors develop improvements to the super shoe technology through their own R&D, it is possible that they may still tread on the toes of Nike’s original IP. Other companies, such as Adidas, have sought further innovation in the field, and their IP will equally be integral to successfully commercialising that innovation.

Whatever the area of technology, and whether you are an innovator looking to establish a market advantage or an adopter looking to enter an existing patent landscape, GJE can help you navigate the various IP issues and maximise the effectiveness of your patent protection.

If you would like to discuss any of the aspects above or get advice on your own intellectual property, please contact Dan Mulryan directly or any of GJE’s patent attorneys at gje@gje.com.

[1] Website press release announcing racing shoe regulations update

[2] Data on shoe brands worn by podium finishers of World Marathon Majors provided by runningshoesguru