Rock climbing is an activity that encompasses many different disciplines. One of the best known of these is “sport climbing”, where the climber attaches their rope to pre-drilled permanent bolts as they ascend, to catch them if they fall. Nowadays, the majority of the most difficult climbs in the world are bolted sport climbing routes, and sport climbing has been an Olympic sport since Tokyo 2020.

However, before drilling of bolts became commonplace in the 1980s, climbers would instead ascend rock faces by placing temporary protection devices to (hopefully) catch them if they were to fall. These temporary protection devices ranged from metal “nuts” or knots of rope jammed into existing cracks in the rock, to small hooks (known as “skyhooks”) precariously balanced on horizontal edges. Unlike bolts, the force of a fall can rip these devices from the rock leading to some unexpectedly large falls. This is exactly as terrifying as it sounds. Nevertheless, this form of climbing (known as traditional or “trad” climbing) is still popular to this day.

While not known for their sense of self-preservation, many climbers devised ingenious ways to make their protection devices more reliable, and one type of device with a particularly interesting story is the “camming device”.

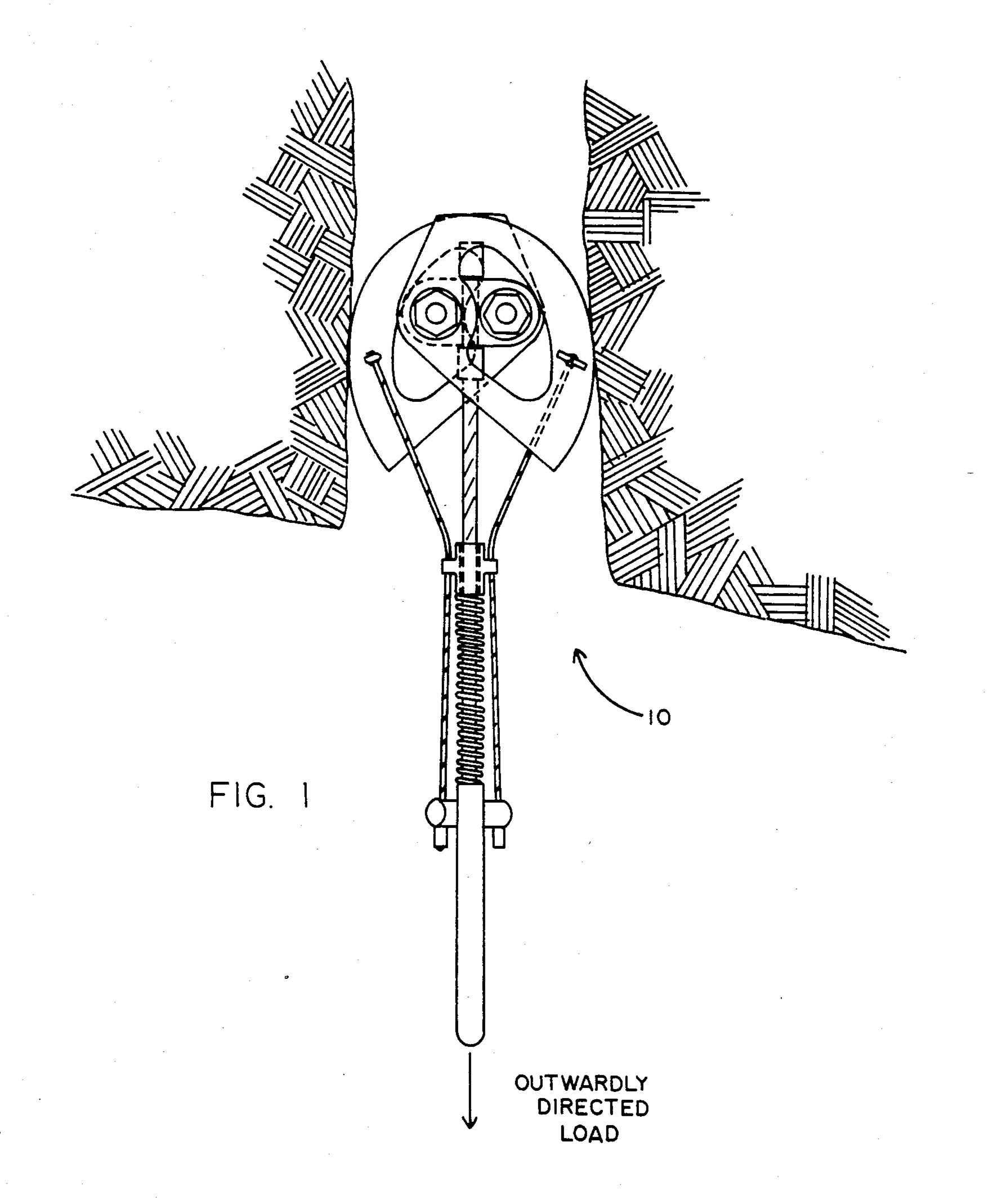

In essence, camming devices are designed to be placed within cracks in the rock and are shaped so that a force pulling the device loose is converted via rotation into an expansion force, thereby locking it more tightly in place in the crack. Such devices are more secure than the use of “nuts” since they are less reliant upon favourable geometry of the rock itself. Modern camming devices are so effective that they can support more than a tonne of weight between two parallel vertical surfaces.

The earliest use of the camming concept is widely attributed to Soviet mountaineer Vitaly Abalakov as early as the 1930s. Further refinements were made by Greg Lowe, who used cams that were shaped such that during rotation within the crack, the gripping surfaces remain at a constant angle with the rock. This allows the cam to lock itself within a range of crack thicknesses while maintaining a consistently strong grip. In August 1973, Lowe applied for a patent for this concept, which was granted in April 1975 (US3877679A).

Around this time, Lowe had also been investigating further improvements to the camming device, including development of some spring-loaded prototypes. However, it was a different American climber, Ray Jardine, who is usually credited with actually making these devices a reality. After years of experimentation and prototypes (including borrowing facilities at the University of Colorado), Jardine arrived at a device that combined multiple camming elements into an easy-to-use spring-loaded unit. The device could be operated with only one hand, and the camming elements could be easily retracted to allow for removal from cracks (which was a problem that existing “passive” devices frequently suffered from). Using these spring-loaded camming devices (“SLCDs”), Jardine was able to climb routes previously considered impossible, not just due to the difficulty of the climbing, but also due to the difficulty of placing protective equipment. One of these routes included what was at the time, the hardest climb in the world (“The Phoenix” – 5.13a).

Perhaps due to the significant advantage his devices gave him on the rock, Jardine did not seem to have any interest in sharing the device with others. On the contrary, in an interview with Mountain Magazine in 1979, Jardine said that “my climbing partners were sworn to secrecy – I’d march my partner to the rock at gun point and make him swear not to say a word… I thought if someone else saw them they’d go rushing out and make them and sell them themselves”. This unorthodox approach to non-disclosure agreements is certainly not something we’d recommend.

Eventually, one of Jardine’s friends encouraged him to commercialise his device, and in January 1978 Jardine applied for a patent (US4184657). When the devices were released onto the market (under product name “Friends”), they were a huge success, so much so that the term “friend” became synonymous with spring loaded camming devices. However, the official release of the device occurred after more than six years of operating the device in secret. Had any of Jardine’s climbing partners ignored his threats and disclosed the device (or if any of the devices were lost or left behind), Jardine’s patent may not have been valid, and he would not have been able to capitalise on what was clearly a hugely sought after device.

Here we reach our first lesson from this story. While non-disclosure agreements (“NDAs”) can be a useful tool to confer confidentiality when discussing your innovation (and are certainly better than nothing), they are not always a fail-safe way to prevent an unwanted disclosure. Instead, if you have a patentable invention that you think may be valuable, then often the best option is to file a patent application as soon as possible. This will remove any doubt over what you invented when, and will prevent disclosures by others made after the filing date of the application from potentially invalidating your patent.

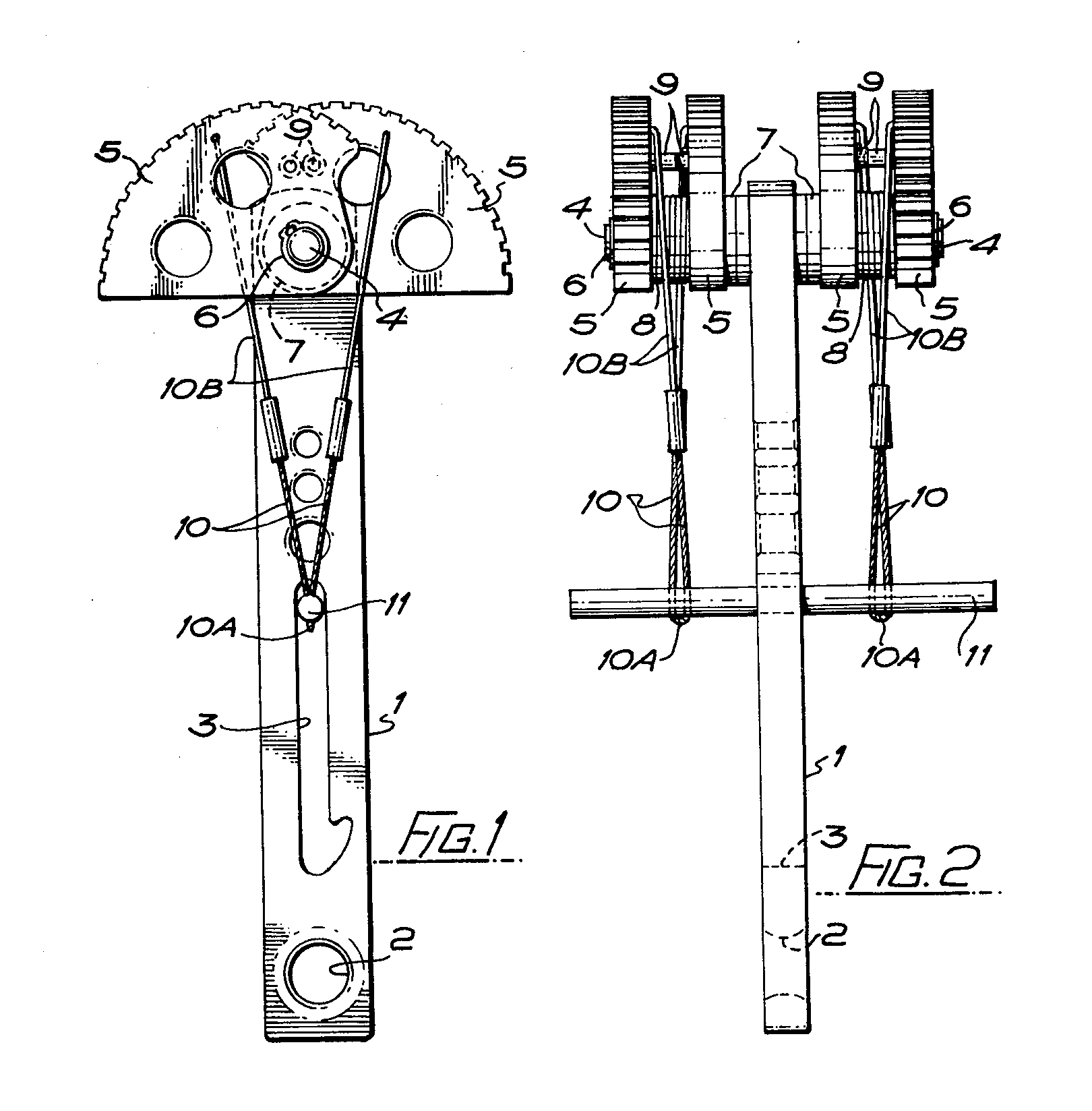

While Jardine did have a patent covering his device, it should be noted that the scope of patent protection is defined by what is “claimed”. In this case, Jardine’s patent essentially claimed the following: a support bar (1), a spindle (4) on the support bar, at least two opposing cams (5) mounted on the spindle, means for urging the cams into an expanded position (8), and a sliding operating bar (11) to actuate rotation of the cams on the spindle.

While this prevented competitors from manufacturing copies of Jardine’s product that fell within the scope of his patent, it is notable that his competitors were quick to develop alternative camming devices.

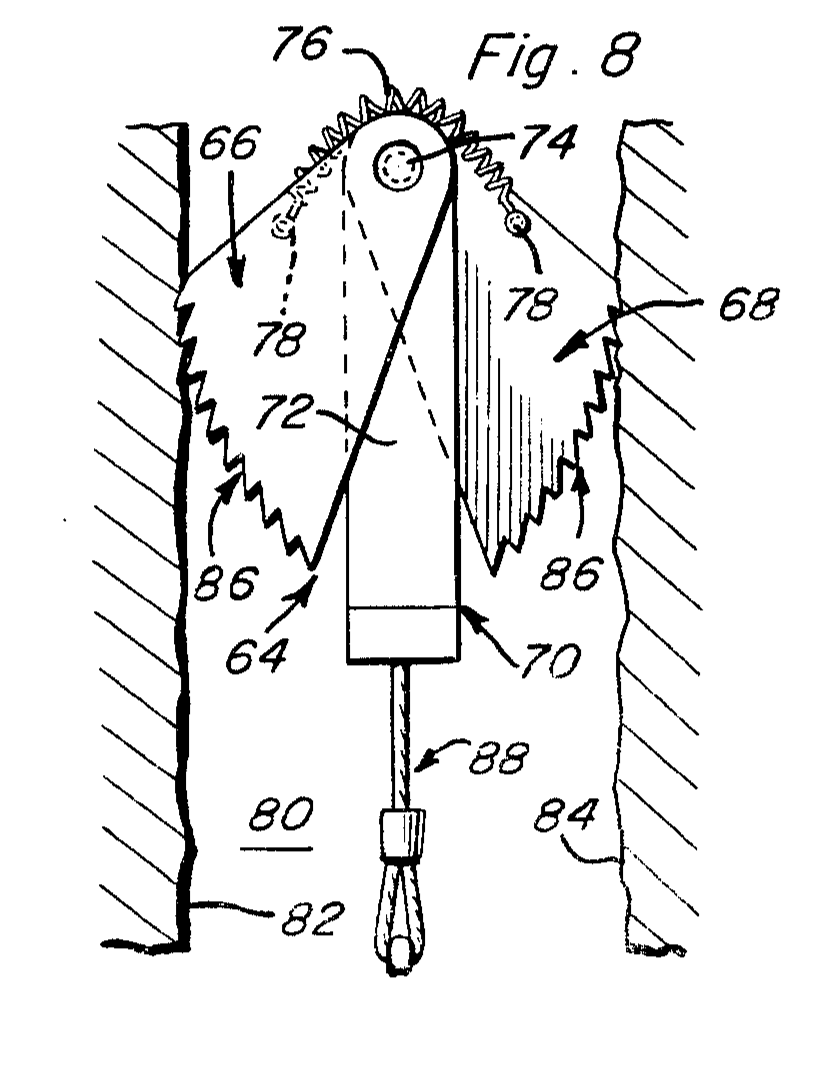

For example, one approach was to replace the “support bar” with a flexible component. Alternatively, some replaced the operating bar with a ring pull mechanism, or changed it from being slidably movable to being rotatably movable. One particularly notable device is the Camelot (still produced by Black Diamond ®), which uses two parallel spindles rather than a common one for all the cams. While some considered this design to be a mere workaround, it does have the benefit of increasing the available expansion range, and in 1985 a patent was filed to protect this innovation (US4643377).

Whether these alternative devices were made deliberately in view of working around Jardine’s patent or were bona fide improvements designed from the ground up, it is likely that Jardine could have stopped at least some of these alternative devices if he had drafted his claim more broadly. While it is difficult in practice to completely prevent any possibility of workarounds, a well-drafted patent claim often covers variations that the inventor did not even realise existed, which allows them to capture a larger slice of the market.

And here we reach our second lesson from this story. Drafting patents is a complex process, and the scope of the claims can be critical to commercial success. Therefore, it is highly recommended that inventors seek the help of a patent attorney when preparing a patent application, and particularly one with a close understanding of their technological field. Doing so will give you the best chance of protecting your invention with the most commercially advantageous scope.

Here at GJE, our patent attorneys are experienced at working with inventors to understand the underlying concept behind their inventions. If you have an invention that you would like to protect or if you would like to discuss anything in this article further, then please contact Alexander Norden, or get in touch with our patents team at gje@gje.com.