Many engineering firms will be aware of how to patent their usual, often “physical”, inventions. However, as more industries transition towards software-implemented solutions, firms can find themselves in new territory where they are uncertain of whether and how to protect their new products.

Imagine, for a moment, a start-up company focusing on marine craft that has happened upon a new and inventive concept during research and development. However, its new concept does not fit into the typical “physical” inventions it has protected before. The new concept is that through the incorporation of geographic and tidal data, it can optimise how unmanned watercraft operate, for example by improving the routing of its craft.

What is unlikely to be protectable

The start-up initially wishes to protect how it sorts the data itself – in other words, the clever algorithm behind its new concept. This is because it uses a machine learning algorithm which it does not believe anyone else has thought of or used before for such a situation. The start-up would like to have broad protection for its new concept, and as such it would like to have protection without the specific inclusion of the application to water-based drones.

However, it is unlikely the company would be able to get this broad concept patented under European patent practice as there is no clear “technical effect” and fundamentally computer programs “as such” are excluded from protection. At the European Patent Office (EPO), a technical solution to a technical problem is required for an invention to be present and it is likely that the sorting of data using machine learning would be seen as a non-technical feature (a computer program “as such”). For example, the data sorting algorithm could have been performed, albeit slowly, by hand and therefore simply speeding this up using known technology would likely be seen as not providing a technical solution. Consequently, while the way the geographic and tidal data is sorted may be new, it is almost certainly not “inventive” under European patent practice.

Similarly, the law in the UK does not allow computer programs “as such” to be protected. The meaning of computer programs “as such” in the machine learning space was recently in question following an IPEC judgment which held that trained artificial neural networks (ANNs) did not engage the “program for a computer” exclusion at all. However, this was overturned on appeal, with the Court of Appeal concluding that a trained ANN in and of itself does involve a computer program and therefore a technical effect linked to the ANN is required for patentability.

What is likely to be protectable

Given the unlikely prospect of protecting the broad concept of its sorting algorithm, it is recommended to the start-up that it includes the context and use of the data sorting method in its application. This might mean for example how it is used to improve how routing is calculated and undertaken by the water drones in use.

Taking such an approach would allow for the concept to be demonstrated to have a technical effect of improving unmanned watercraft routing (saving power, for example). Under both UK and EPO practice, it would therefore be more likely be accepted that a patentable invention may be present in the application. This is because features which when taken on their own are not technical, but when combined with others result in a technical effect within the context of the invention as a whole, can generally be used to demonstrate that a concept can be protected via a patent.

Therefore, even though the new and clever part of the concept is purely software-based (geographic and tidal data sorting using machine learning), it could be argued to be inventive in the UK and the EPO. Using European practice language, it provides a technical solution (improved routing) to a technical problem (a reduction in resources used) within the technical context of unmanned watercraft. In UK practice language, it provides a “real-world” effect outside of a computer.

Does this mean that the sorting algorithm can be copied by competitors without infringing?

While a claim that makes no mention or allusion to the technical use of the sorting is not likely to be patentable, it should be possible to formulate the patent claim language such that an unmanned watercraft itself is not claimed and only the sorting method is claimed. This can be achieved by including the technical way in which the sorting is used (watercraft routing) in the preamble of the claim, so providing the required context. This way, the start-up would be protected from a competitor merely sorting the data in the new and clever way and providing it to a third party for the actual physical implementation.

Therefore, while traditionally the firm may have considered only protecting this new concept via keeping it a trade secret, it now realises that patent protection is an entirely viable option to be explored and exploited.

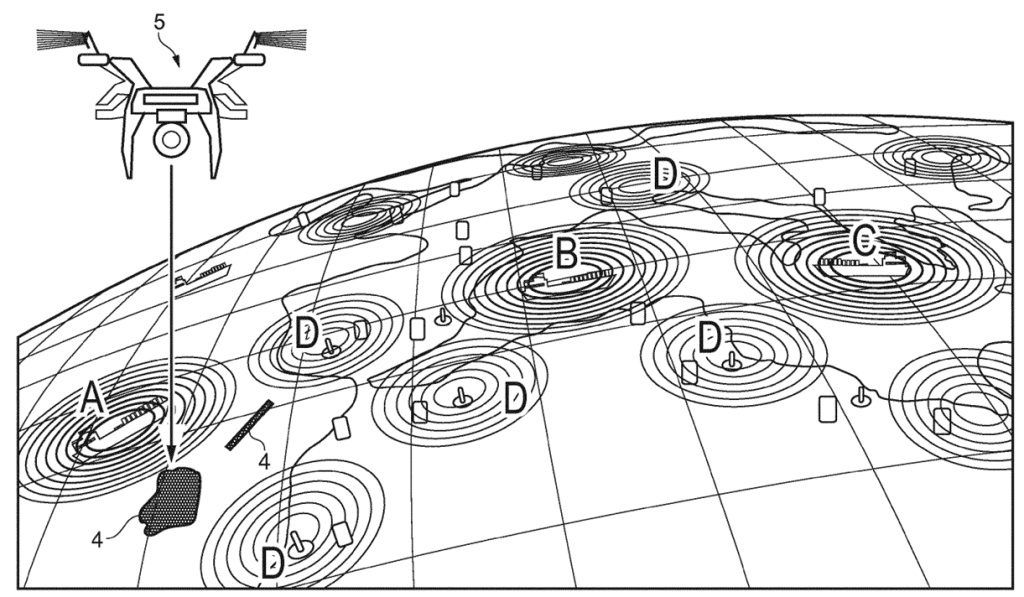

A real-world example of a similar concept being patented at the EPO, is Rolls Royce’s European (EP) patent (EP3376488B1) for obstacle map generation for use in navigating one or more vessels.

The claimed invention in this European (EP) patent updates an obstacle avoidance map in real-time via data collected from a ship’s sensor. It should be noted that the preamble of the patent specifically states that the generated map is used for “the navigation of one or more vessels” and therefore provides the context for the technical problem and solution, but importantly also does not claim an actual vessel.

In conclusion, while software-based inventions which provide a technical effect are patentable, it can be a more nuanced process than a more “typical” engineering invention. When seeking protection for such inventions, it is important to remember that a “technical effect” is required under UK and European practice in order to achieve patent protection.

Given how quickly this area of law is changing, especially in the UK, it is vital that you receive up-to-date legal advice that is in line with current case law and practice. If you have a software-based invention and are unsure as to how to protect it, please email us at gje@gje.com.