If you have ever been perplexed as to why your patent attorney keeps talking about windsurfing, you might be surprised to learn that the origins of windsurfing have played a key role in shaping UK patent law as we know it. A landmark decision in Windsurfing International v Tabur Marine (1985) still informs how the matter of inventive step is assessed today.

In that case, the Court of Appeal was called upon to determine whether Windsurfing International’s patent (GB1258317A) was ‘obvious’ (i.e. lacked an inventive step) in view of the knowledge and technology of the time. In that assessment, they formulated a four-step approach which established the precedent for how that question of obviousness should be decided [1].

Put succinctly [2], the four-step Windsurfing approach involved (1) identifying the inventive concept of the patent in question; (2) determining what a person skilled in the art would have known at the time of the patent’s first filing; (3) identifying any differences between the claimed invention and any matter cited as being “known or used” before the date of first filing; and (4) deciding, without any knowledge of the claimed invention, whether those differences would have been obvious to the skilled person or whether they require an inventive step.

In the case of Windsurfing International v Tabur Marine (1985), Windsurfing International’s patent was found to be obvious in view of a fairly unconventional piece of prior art – the invention by a 12-year-old boy, Peter Chilvers. Chilvers is credited as an early windsurfing pioneer and, in 1958, at only 12 years old, he built his first ‘sail board’ at his home on Hayling Island [3].

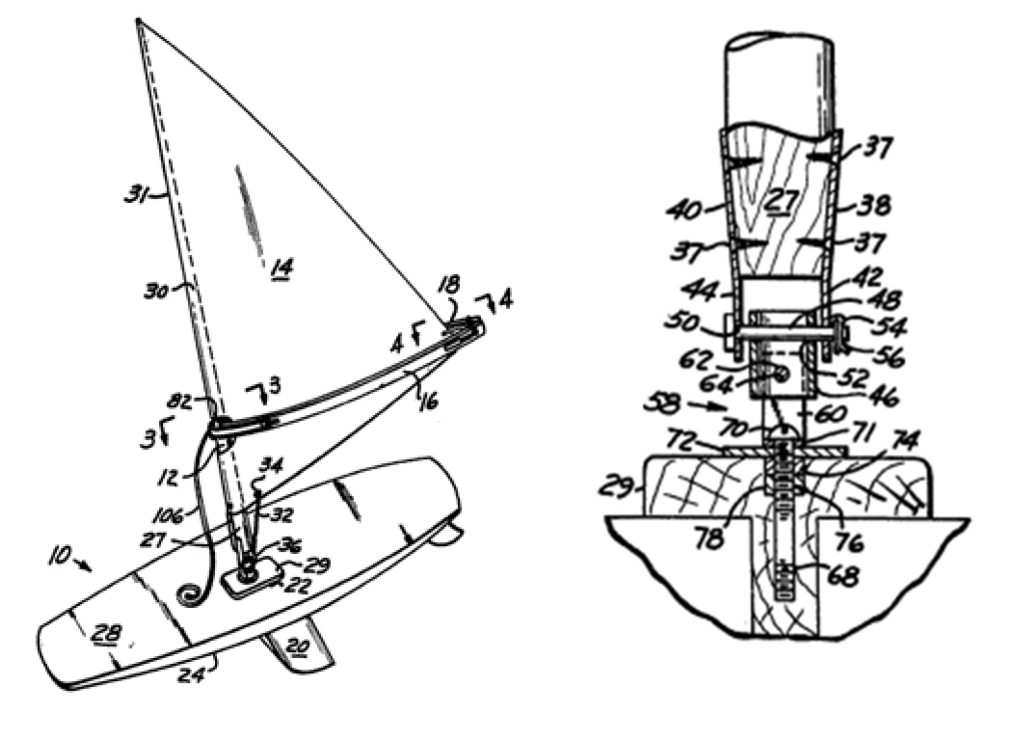

The Court of Appeal identified, as per step (3) of its four-step approach, that the only difference between Chilvers’ ‘sail board’ and Windsurfing International’s ‘Windsurfer’ was that Windsurfing International claimed “a pair of arcuate booms” (see Figure 1, reference numeral 16), whereas Chilver’s booms were flat when not in use (although it was postulated that they might bend and become more arcuate in use). The Court found, in applying step (4), that the use of arcuate booms was indeed obvious, and Windsurfing International’s patent was revoked.

Figure 1 (left) and Figure 2 (right) of GB1258317

There were, however, further differences between the ‘Windsurfer’ and Chilvers’ ‘sail board’. Chilvers’ board had a ring on the deck to which a hook at the foot of the mast could attach (3), whereas the Windsurfer utilised a more traditional universal joint, depicted in Figure 2 of the patent. Additionally, Chilver’s first sail board was also more akin to the hull of a small dinghy whereas the Windsurfer’s was based on a surfboard and more in line with modern windsurfing boards.

Unfortunately for Windsurfing International, it had no claim directed towards the board itself and when, in the late stages of the infringement proceedings, they attempted to limit their claims to the combination of their hand-held rig with a ‘surfboard hull’, the Court of Appeal refused this limitation on the grounds that it was too late in the proceedings to raise new issues.

This loss for Windsurfing International was perhaps a win for windsurfing as a sport. Tabur Marine, now BIC Sport (yes, as in BIC pens) continues to produce windsurfing boards to this day. Indeed, BIC Sport designed the Techno 293, the official windsurfer for the Youth Olympic Games and innovation elsewhere in windsurfing does not show any signs of slowing down.

The explosion of foiling across all water sports, from the America’s cup to the ever-growing popularity of wing foiling, has finally made its way into windsurfing at the Olympics with the introduction of the iQFoil as the official windsurfing class of the Paris 2024 Olympics.

If you’ve watched any of the windsurfing at these Olympics, you’ll certainly be able to identify some differences between the iQFoil and Windsurfing International’s ‘Windsurfer’. These differences may be novel, but if you want to ask yourself whether they are inventive, consider applying the four-step Windsurfing approach.

If you would like to discuss any of the issues raised in this article, or if you have any questions about patent protection then please email us at gje@gje.com.

[1] This precedent was updated when Pozzoli SPA v BDMO SA [2007] EWCA Civ 588reformulated the four-step Windsurfing test. The current standard for assessing obviousness is the combined Windsurfing/Pozzoli approach (section 3.13 of the Manual of Patent Practice).

[2] The full four-step Windsurfing approach is set out in section 3.11 of the Manual of Patent Practice

[3] P – Peter Chilvers: inventor of the windsurfer – Windsurfing UK (windsurfingukmag.co.uk)