…or a tale of when and how not to disclose ahead of an EU registered design filing.

In 2014, Rihanna may have been better known for her music career. But in 2024, Rihanna is now a powerhouse in the cosmetics and clothing industries at the helm of Fenty Beauty and Savage X Fenty brands, and having previously led the former Fenty fashion house. So, in hindsight, Rihanna being the focus of an invalidity case against a European Registered Community Design (RCD) directed to shoes, while inadvertent, is not surprising. The case also demonstrates the effect of social media platforms on rights created from laws written well before the social media age.

In summary, Puma v EUIPO in T-647/22 at the General Court of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) involved a December 2014 disclosure on Instagram and a fan website of Rihanna wearing shoes subject to an RCD filing in July 2016 with a priority date in the same month. The Court upheld that, this being well outside the 12-month grace period discounting rights owners, or related, disclosures caused, the design was invalid.

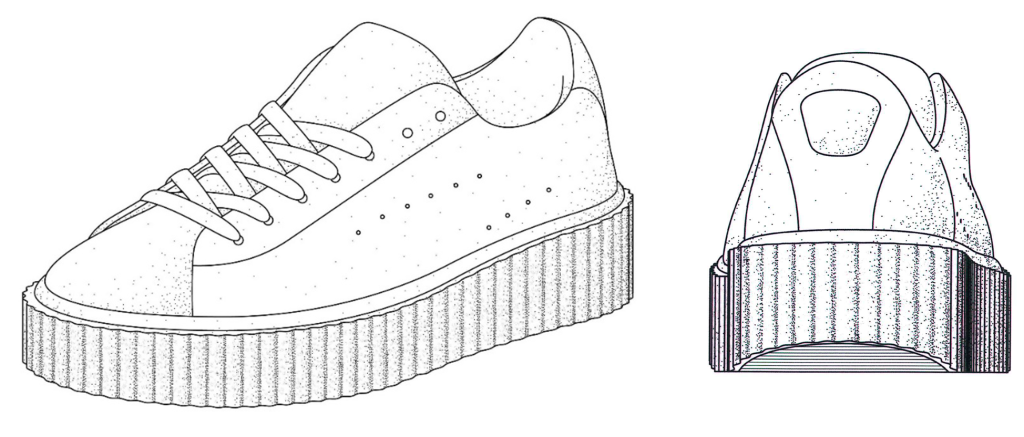

Views 1 and 3 from Puma’s European Registered Community Design 0033250555-0002

The case focused on whether the Instagram posts held enough detail to meet the criteria for a disclosure. This entailed also assessing whether that, then, met the slightly obscure requirement of whether the disclosure could have ‘become known in the normal course of business to the circles specialised in the sector concerned’ (Article 7(1), first sentence, Council Regulation (EC) 6/2002).

Tackling the final point was easy. Most of the disclosures were made on Rihanna’s own Instagram account, @badgalriri – these can be seen below – and, undoubtedly, what Rihanna and other celebrities were wearing in 2014 was of interest to their fans. From there, it is not a stretch that Riri’s fans could include members of the fashion industry at that time, making the logic trail quite simple.

The point that requires a little more Work was whether the shoes were shown in enough detail to form a sufficiently complete disclosure that could then be compared to the registered design. This ultimately came down to the Instagram posts not quite showing the whole shoe across all the photographs. In particular, a small section of the back of the shoes is not visible in sufficient detail in any image. Additionally, while the design is directed to the right shoe, the most significant disclosure of the shoe back was of the left shoe.

In the decision, the General Court set out one position that ‘the disclosure of an earlier design cannot be proved by means of probabilities or suppositions, but must be demonstrated by solid and objective evidence that proves effective disclosure of the earlier design’ (see paragraph 34 of T-647/22). The Court then appear to depart from this position by acknowledging that the back of the left shoe is ‘not perceptible’ (see paragraph 49 of T-647/22) but further state, ‘there is no reason to infer that the right shoe would be different from the left shoe’ and that the shoes are clearly ‘a pair of uniform shoes’.

While some may see this as dubious logic, the conclusion is a practical one. In other words, it is likely a registered design directed to a right shoe would be considered to lack individual character over a left shoe that is otherwise identical solely based on which foot the shoe fits.

The decision is potentially Unfaithful to the case law on the fullness of disclosure needed to allow a piece of prior art to be used against a registered design. However, considering all the Instagram posts reproduced in this article, this is close to the line, but likely the decision came down on the correct side, just potentially with a less full explanation than could have been provided. The creative director’s post above, for example, shows a side-on view of the right shoe, showing the entire length of the shoe’s back.

This will not be the last time social media posts cause issues for registered designs. However, measures can be taken to ensure they Don’t Stop the Music. So, turning to what can be learnt from this case and how it may affect filing strategies, primarily, this case firmly sets out that a disclosure in one social media post, or spread across several posts, can act as prior art against a registered design, and the extent of the grace period is reaffirmed. Further, there is some flex, at least for now, in needing to provide ‘solid and objective evidence’ for a disclosure.

These points mean disclosures in social media posts should be closely tracked by those responsible for design filings. Where possible, coordination between marketing and social media managers and the legal team would be recommended if every legal team did not already want more of that (or to just be the social media managers themselves!). When a disclosure does happen, even if it is not a complete disclosure of the article, any registered designs should be filed within a year of the disclosure and, as always, preferably as soon as possible.

This case could still go in front of the CJEU. And with the recent LKQ Corp v QM judgment in the US causing waves, potentially altering the assessment on challenging the parallel US design patent, future developments may mean there are still some legal Diamonds in store.

For further information on how to protect your products with designs, or if you have any questions in relation to this article, please find my contact details on my website profile or contact our dedicated designs team at gje@gje.com.

ahttps://www.instagram.com/p/wrSdiuBM49/

bhttps://www.instagram.com/p/wq5DCXhMxk/