This is the third case in our series of three in which we examine recent UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) trade mark opposition decisions where major brands enforced their reputations and goodwill against applications filed by smaller companies. This article concerns energy drink brand Monster Energy and an opposition it filed (O/0482/24) against the trade mark Codice Citra for wines and alcoholic beverages. The first two articles involved Ocado and JD Sports.

Where the Ocado and JD Sports cases demonstrated how far a reputation can stretch, this case identifies some of the limits.

Monster Energy alleged that there was a likelihood of confusion between the marks and that its earlier trade marks enjoyed a reputation that the application would take unfair advantage of. Monster also called on unregistered rights.

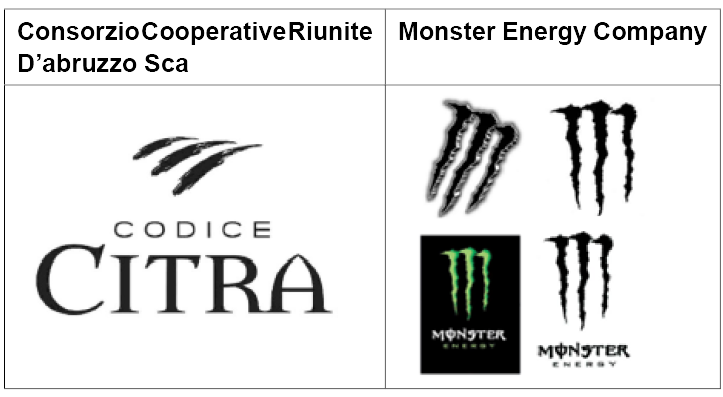

The respective trade marks are as follows:

Monster Energy faced a number of hurdles. The first was the differences between the goods. The UKIPO undertook a careful comparison of energy drinks and alcohol noting that those goods are “different in a key respect” in that whilst “alcoholic drinks may be consumed for refreshment purposes, they are always consumed at least partly for the effect of the alcohol”. The goods are also not in competition and are not complementary because “the average consumer would not expect the same undertaking to be responsible for the goods” and the goods would not be sold in the same aisles in a supermarket. Therefore, the hearing officer found the goods to be dissimilar.

On an analysis of the applicant’s mark, the UKIPO noted that “The eye is naturally drawn to the element of the mark that can be read… [and so] the word CITRA plays the greater role in the overall impression”. As for a comparison of the respective devices, ultimately they were seen to differ visually given the inclusion of the words and the marks were also found to be aurally and conceptually dissimilar. Consequently, Monster’s argument for a likelihood of confusion was unsuccessful, as was its claim based on unregistered rights for the same reasons.

Monster was able to persuade the UKIPO that it enjoys a strong reputation in the UK but given the differences between the marks, no “link” or connection was found to exist between them in the minds of the relevant public.

Conclusion

The case serves as an interesting counterpoint to the Ocado and JD Sports decisions and demonstrates that there is a limit on the scope of protection afforded to even the most successful brands. Monster could not overcome the fact that fundamentally the marks were different and as such there was no likelihood of confusion, nor any sort of unfair advantage enjoyed by the applicant.

It is worth remembering that even when one party is a large and famous brand, that does not guarantee success and that a careful analysis of the respective trade marks and goods and services is vital before deciding whether or not to contest a matter.

If you would like to discuss any aspect of trade mark law or get advice on your own intellectual property, please contact Edward Carstairs or any of GJE’s attorneys at gje@gje.com.