A recent decision of the UK High Court illustrates reasons why it is often preferable to register your designs rather than relying on unregistered design protection alone.

Rothy’s Inc, and subsequently Giesswein Walkwaren AG, both marketed “ballet flat”-type shoes made from knitted recycled plastic, a material not previously used for this type of shoe. Rothy’s Inc had registered design protection via a Registered (EU) Community Design, RCD, for its Pointed Loafer design, and also believed its product qualified for unregistered design protection as an Unregistered (EU) Community Design, UCD.

Based on this design protection, Rothy’s brought an action of infringement against Giesswein, who counterclaimed for invalidity. In deciding that Rothy’s designs were valid, and that Giesswein’s ballet flat infringed Rothy’s RCD, the UK High Court covered some interesting points of designs practice in Rothy’s v Giesswein [2020] EWHC 3391.

Proving Copying

Fashion is a fast-paced industry, where a given design may only be used for a short run. On this basis, some companies choose to minimise their costs for design protection by relying on unregistered design protection, which exists automatically – similar to copyright – for a limited term of protection based on when a product encompassing that design was first marketed. For example, unregistered design protection was recently used successfully to prove infringement of shapewear jeans at the UK High Court in Freddy SPA v Hugz Clothing Ltd & Ors [2020] EWHC 3032.

It is no surprise then that when Rothy’s Inc found Giesswein selling a shoe that looked remarkably similar to their Pointed Loafer, they alleged that Giesswein had infringed their unregistered design protection for the Pointed Loafer. However, while unregistered design protection is automatic, a key hurdle you must overcome during enforcement is proving that the alleged infringing article was the result of actual copying of the unregistered design, rather than the other party simply arriving at it independently.

Even if it is clear that two designs are very similar, the need to prove copying can make unregistered design protection difficult to enforce. In the present case, the parties agreed that a ballet flat shoe according to the unregistered design (the “Pointed Loafer”) was sold on Rothy’s website, and that Giesswein was aware of Rothy’s as a designer of similar shoes, had inspected shoes on Rothy’s website, and indeed had on several occasions bought all available shoe designs from Rothy’s website.

Nevertheless, the court decided that it was not established that Giesswein had the opportunity to copy the Pointed Loafer. One reason for this was that the court noted that the Pointed Loafer was a short run product, only available on the Rothy’s website for a short period of time. So, while a short run could have been used to justify Rothy’s relying on unregistered design protection, the short run itself undermined enforceability of the unregistered design protection and as a result, Rothy’s claim of infringement based on its unregistered design failed.

Significance of drawings in interpreting designs

Fortunately for Rothy’s, they had also registered their design, giving them a second enforcement option, with which they had more success.

Unlike unregistered designs, registered designs do not require any copying to be infringed. The key question for deciding on infringement of a registered design is whether the alleged infringing article provides the same overall impression as the design. However, despite the focus on overall impression, this judgement reminds us that the fine details of drawings can be very important when interpreting the subject-matter of a registered design.

It was agreed that Rothy’s were the first to market “ballet flat”-type shoes made from knitted recycled plastic. However, Giesswein argued that the Rothy’s registered design was invalid in view of earlier ballet flat shoes made from other materials such as suede, meaning that the design protection should not be enforced. A key question for the court was whether the new material of knitted recycled plastic was part of Rothy’s registered design.

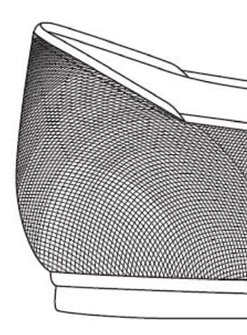

To answer this question, as ever with designs, it was necessary to assess the design drawings to determine whether the material is shown. As shown below, the design drawings include crossed lines, which was argued by Giesswein could be there for any number of reasons.

In the decision, the specific layout of lines was considered, and it was found that this layout was inconsistent with suede, and only consistent with a knitted fabric, which was capable of giving a different overall impression from prior art. Rothy’s registered design was therefore found to be valid over prior art constructed from other materials and was considered to be infringed by Giesswein.

Key Takeaways

Given how difficult it can be to enforce an unregistered design, even in a case such as this, where the infringer admitted to monitoring the designer’s product line, it is highly recommended to protect your designs using registered protection.

The representations are all important in registered designs, and while there was some discussion of other elements of the shoe shape in Rothy’s registered design, in the prior art, and the infringing article, it is striking that the finding of validity and infringement was mostly based on the material inferred from the cross-hatching. So, if you are registering a design it is important to ensure that all details to be included in (or indeed excluded from) the drawings are carefully considered at the time of filing the application.

If you would like to know more about obtaining registered protection for your designs, please find my contact details here contact us at gje@gje.com.