Olympic rowing has created some dramatic races and stories over years. Steve Redgrave winning his 5th Olympic Gold in Sydney, Matthew Pinsent’s podium tears in Athens, Katherine Grainger finally winning Gold in front of a home crowd in 2012 and the all-conquering Kiwi pair, to name just a few, all evoke strong memories (for me at least!).

This year’s Olympic rowers will all be vying for similar glory over a 2000m stretch of the Vaires-sur-Marne Nautical Stadium, to the east of Paris. Although the medals are ultimately won and lost on the water in fragile carbon boats that require a surprising amount of balancing to avoid capsizing or the dreaded “catching a crab”, all of the competitors will have spent many hours on dry land honing their skills on the rowing machine. Indeed, the rowing machine was a fundamental part of my own Olympic campaign in Rio 2016 (but that’s another story).

An unbeatable foe, the “ergo”, to use common rowing parlance, is generally seen as rather dull, if incredibly effective, piece of equipment that needs to be endured. You simply pull on the handle – perhaps a little bit harder if your coach happens to be walking past – and hope that the numbers on that little LCD display staring back at you don’t get any slower. There’s a little more nuance to it than that, but you get the gist.

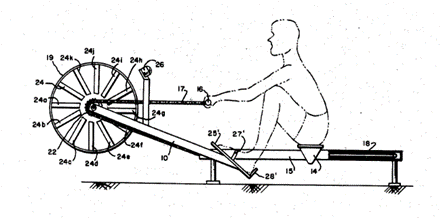

To rowers and gym-goers alike, the Concept II ergo will likely be the piece of kit that springs to mind when thinking about rowing machines. Devised by the Dreissigacker brothers together with Jonathan Williams, they filed a patent (US4396188) in 1981 for a “Stationary Rowing Unit”, which became known as the Model A machine. There may even be one hidden in your garage somewhere.

Further developments continued, including the “dynamic erg” intended to more closely simulate the feeling of rowing in a boat (the subject to US patent applications US2012/0100965 and US2011082015), and we are now on to Model E machines, where users will recognise the images of EU registered design 008538870-003 that protects the visual appearance of the machine.

Another brand of rowing machine, WaterRower, is making waves in the IP world. Devised by engineer and former rower John Duke, in addition to replicating the experience of rowing in a boat, a key principle of the WaterRower is to create a piece of “Fitness Furniture” that provides the user with a “welcoming emotional connection”. In contrast to the metal and plastic of the Concept II machines, the WaterRower has a wooden frame to help achieve the aesthetic goals, and has become an iconic design, featuring in numerous publications and in the TV series House of Cards. It has been displayed at London’s Design Museum and you can even buy it from the MoMA design store.

In 1987 Duke applied for a patent US4846460A to protect the technical function of the machine. Although the patent has long since expired (patents last 20 years from filing), WaterRower is now claiming copyright infringement of their machine by Liking Limited (trading as TOPIOM) under the protections of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988. TOPIOM admits to having copied WaterRower’s machine, but sought to strike out the Claimant’s claim on the basis that the WaterRower did not meet the requirements to be a “work of artistic craftsmanship” within the meaning of s.4(1)(c) CDPA 1988.

The judge refused to strike out the claim (the judgment can be found here), holding that the claimant has a real prospect of proving that the WaterRower has a real artistic or aesthetic quality, beyond simply being appealing to the eye. The subsequent trial judgment will be eagerly anticipated in the UK (it is now a year since the trial date), particularly given the apparent divergence between UK and retained EU law on this point of artistic craftsmanship.

This raises some interesting points about IP strategies for protecting your invention. The difficulty in relying on copyright highlights the importance of effective patent protection, which can be enforced so long as a third party’s product falls within the scope of the (valid) claims. As patent protection expires after 20 years, further strategies may be employed to maintain enforceable IP rights, including registered design protection for new aspects (as exemplified by Concept II’s designs and WaterRower’s own EU registered design here), effective brand protection through registered trade marks, and, of course further innovation that may give rise to further patents. There is generally no “one size fits all” approach to IP strategy, and we advise that you speak with a qualified patent attorney to determine how best to protect your invention.

The interaction between the various IP rights lying behind rowing machines may not be front and centre of the athletes’ minds as they fight for medals in Paris, but it has played a significant part in getting them to the start line.