Until recently there has been no way to obtain a single patent right covering several European countries. However, the framework surrounding patent protection in Europe is changing. The new Unitary Patent (UP) system will enable applicants to obtain a single patent right covering several EU jurisdictions and, following a recent announcement, is now planned to come into force on 1 June 2023. Many companies should now start to evaluate how best to approach these new aspects of patent protection in Europe.

In this article, we provide a brief outline of the UP and discuss some strategic factors that companies might consider when deciding their approach to UPs by looking at the biomedical engineering sector as a case study.

The Unitary Patent

Previously, the next best thing to European-wide protection with a single patent right was the European patent, which provides a bundle of individual national rights. On grant of a European patent application centrally by the European Patent Office (EPO), it is necessary to validate and maintain the patent separately in each of the member states of the EPO in which protection is wanted.

Once the UP system comes into force, applicants will be able to choose to request the creation of a UP within one month of a European patent being granted through the current EPO system. In contrast to the traditional validation process, UPs will cover all EU member states participating in the UP system (currently 17[1], expected to include a further 8[2], out of the current 38 EPO member states). Therefore, applicants will soon be faced with the important choice between having a UP covering the EU member states participating in the UP system and validating separately in each of these states.

In the wake of Brexit, the UK withdrew from the UP system, which is tied to the European Union, and thus it will not be possible to obtain patent protection in the UK via a UP. However, UK protection can still be obtained in parallel with UP protection by validating a European patent using the existing process. The same applies for other EPO states that (so far) have declined to join the UP system, such as Spain, or are not members of the European Union, such as Turkey.

Once in force, a UP will be renewed each year using a single renewal fee payable centrally at the EPO covering all UP states. The UP will also be enforced and invalidated as a single right through the Unified Patent Court (UPC), a new pan-European court. This makes it easier to obtain more widespread patent coverage and enforcement in Europe; however, this comes together with the risk of central revocation in the participating EU states alongside other important implications.

Strategic Considerations

Costs are usually a central concern for small and large entities alike. Obtaining and maintaining post-grant protection using a European patent involves three main cost-sources. Validation fees are fees associated with entering the European patent onto a chosen national register. Translation fees are required in some jurisdictions to complete validation. Renewal fees are also required each year in each jurisdiction to keep the patent in force.

A common approach for controlling cost is to maintain granted patents only in the UK, France and Germany, as validation can be completed in these economically important states using only the translations already obtained to complete the patent application process. An interesting comparison is to consider the cumulative cost of this common approach with validating and maintaining a UP together with a European patent validated in the UK. This latter approach still covers the UK, France and Germany, but also comes with the additional coverage of 15 other participating EU states.

According to a conservative cost analysis performed at Gill Jennings & Every, the cumulative cost of the UP approach breaks even with the common approach after three years from grant, assuming the application grants 6 years from filing. After this point, the UP approach is less expensive despite the additional patent coverage in 15 states. This is partly due to the deliberately competitive renewal fees that have been set for UPs to encourage uptake of the system and provide a more accessible European patent framework.

Therefore, in terms of cost, the UP system could offer value for money even for applicants following the simple approach of maintaining patents only in the UK, France and Germany. Of course, applicants currently validating and maintaining patents in participating states more widely than just France and Germany could see additional and more immediate cost benefits.

However, notwithstanding these potential cost benefits, there are other important factors that should be considered before deciding to request a UP for all of your European applications granted after the UP system comes into force, as summarised in Table 1.

| Traditional European Patents | Unitary Patents | |

| Enforcement | Infringement proceedings must be brought separately in each EPO state. | Enforced centrally at the UPC for infringements in one or more UPC states at the same time. |

| Invalidation | Can be invalidated centrally using an opposition up to 9 months from grant – but must be invalidated in each jurisdiction individually thereafter. | Invalidated centrally at the UPC, risking loss of protection in all UPC states at once, unless defended successfully. Separate proceedings still required in non-UPC states. |

| Validations & Renewals | Handled separately in each EPO state, meaning some states can be allowed to lapse to trim costs, but more expensive per jurisdiction. | Can only be renewed centrally as a single right but can provide more widespread protection at a lower cost per jurisdiction. |

| Transfers & Licensing | Can be licensed or assigned to different parties in different EPO states. | Can be licensed to different parties in different UP states, but is assigned as a single unitary right. |

Validation and Renewal in the Biomedical Engineering Sector

A natural follow-up question is: how widely do real patent proprietors actually validate and maintain their patents in Europe? For various reasons, such as the geographical distribution of sales or manufacturing, patent validation strategy can differ widely between different technology sectors. A sector-specific analysis provides a more insightful overview of the different approaches taken by proprietors in the same field.

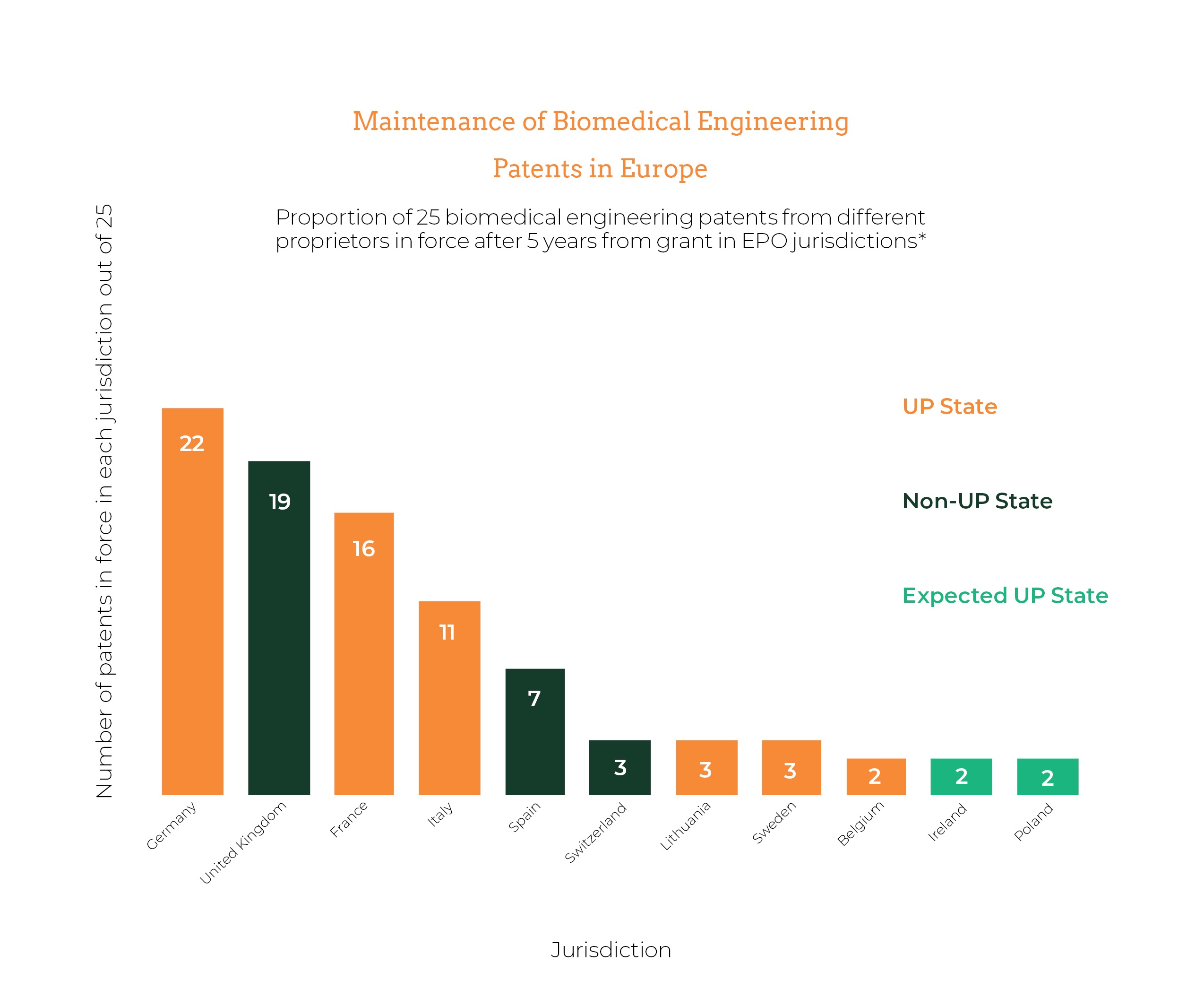

To answer this question, therefore, we investigated a cross-section of 25 European patents granted in 2017 to different biomedical engineering applicants and tallied the EPO states in which these patents remained in force at the time of writing. Nevertheless, we believe that clear parallels can be drawn between biomedical engineering and many other sectors. Thus, the points below could apply equally to companies in similar positions in different sectors.

Figure 1 shows the results for each country with participating UP states coloured red and non-participating states coloured blue. States expected to fully participate in the UP system soon are coloured orange. For this cross-section of this sector, Germany was the most important jurisdiction, with 22 out of a possible 25 of the investigated patents remaining in force at the time of writing. Patents were maintained in Germany, the UK, France, Italy and, to a lesser extent, Spain, notably more often than in other EPO states. In some other EPO member states not shown in Figure 1, only one or two of the 25 patents were maintained, and these tended to correspond to the same one or two patents maintained very widely across several EPO states.

One noteworthy jurisdiction is Italy, in which 11 out of the 25 patents have been maintained. As a UP state, biomedical engineering proprietors seeking protection in Italy may be well placed to make further cost savings with the UPC, based on the cost analysis performed at Gill Jennings & Every. It is also interesting to note that out of the 25 patents, 15 (60%) remained in force in all of France, the UK and Germany 5 years from grant. These proprietors would also be well placed to make significant cost savings, especially if protection is sought in additional participating UP states.

Though these 25 patents represent a small fraction of the number of biomedical engineering patents granted each year, our findings show that many real businesses in this sector could leverage the UP system to obtain wider protection at lower costs. Indeed, we may see the commencement of the UP system influencing the distribution of biomedical engineering patent protection across Europe in the near future.

However, as noted above with reference to Table 1, there are other considerations to take into account, and we illustrate some of these aspects below using case studies of three hypothetical Biomedical Engineering companies. Again, similar considerations to those discussed below would apply to companies in other sectors.

Company-Specific Case Studies

Case Study 1: Company A is a small start-up that has a European patent application based on a new prosthetic implant that is central to their business. Company A thinks that obtaining protection in many EU jurisdictions will increase the attractiveness of the business to potential buyers and investors. Company A is therefore considering whether to validate the patent in several jurisdictions individually, or whether to choose to request a UP upon grant of the application.

In this case, the application is of central importance to the business. Choosing to use the UP system offers more widespread protection but comes at the risk of central revocation, meaning a patent resulting from the application could be invalidated in several key states in a single revocation action. In contrast, choosing the traditional validation route preserves protection in other participating states even if the patent is challenged successfully in one participating state. Company A should carefully consider the extent to which the extra coverage provides attractiveness to investors over the accompanying central revocation risk.

Case Study 2: Company B is a medium enterprise that develops medical imaging devices. Company B has a few key patent applications and some ancillary patent applications relating to non-essential features of their devices. Company B utilises their patent portfolio as a revenue stream through licensing.

Here, Company B may also prefer to avoid the risk of central revocation for their key applications. However, those applications of less central importance may be well-suited for making use of the extra geographic coverage offered by UPs without generating undue risk. A further consideration for Company B is that of licensing. If Company B tends to engage in licensing across several states, then the extra patent coverage could be a lucrative way to open additional revenue streams. Company B could therefore choose to lean towards choosing to request UPs.

Case Study 3: Company C is a multi-national corporation with a large patent portfolio in various health engineering sub-sectors. Company C is involved in some competitive fields in which granted patents are commonly opposed or attacked.

Company C operates in contentious areas, and thus may have to consider further questions such as: will the additional patent coverage interfere with (previously non-competing) companies operating in other UP jurisdictions? If so, Company C may have to consider in turn whether this is likely to provoke resistance from such entities in the form of oppositions or central revocation attacks.

Due to their large patent portfolio, Company C may also be dissuaded from utilising UPs because renewal fees cannot be paid selectively in different participating states to trim patent maintenance costs, in contrast to traditional European patents. This cost-inflexibility means that Company C would be unlikely to want to choose the UP system for all their applications granted after the UP system comes into force. As in the previous examples, a case-by-case approach based on the technology covered by each patent and its degree of relevance to Company C’s undertakings would be more appropriate.

What will you do?

The UP system is intended to reduce costs and simplify the patent process in Europe by centralising validation, renewal, enforcement, and revocation of European patents. However, as we have seen from these examples, the consequences of using the UP system are not so straightforward. A tailored approach based on the merits of each case is warranted to determine whether the extra jurisdictional coverage is worth the reduced flexibility and higher risk brought by the possibility of central revocation. Will you choose to use UPs, or will you stick to the traditional approach?

If you would like to discuss any of the issues discussed in this report with regards to your own patent portfolio, you can find our contact details here and here. To get in touch with our Biomedical Engineering or Unitary Patent team, please email: gje@gje.com.

[1] Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia and Sweden. [2] Cyprus, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Poland, Romania, Slovakia